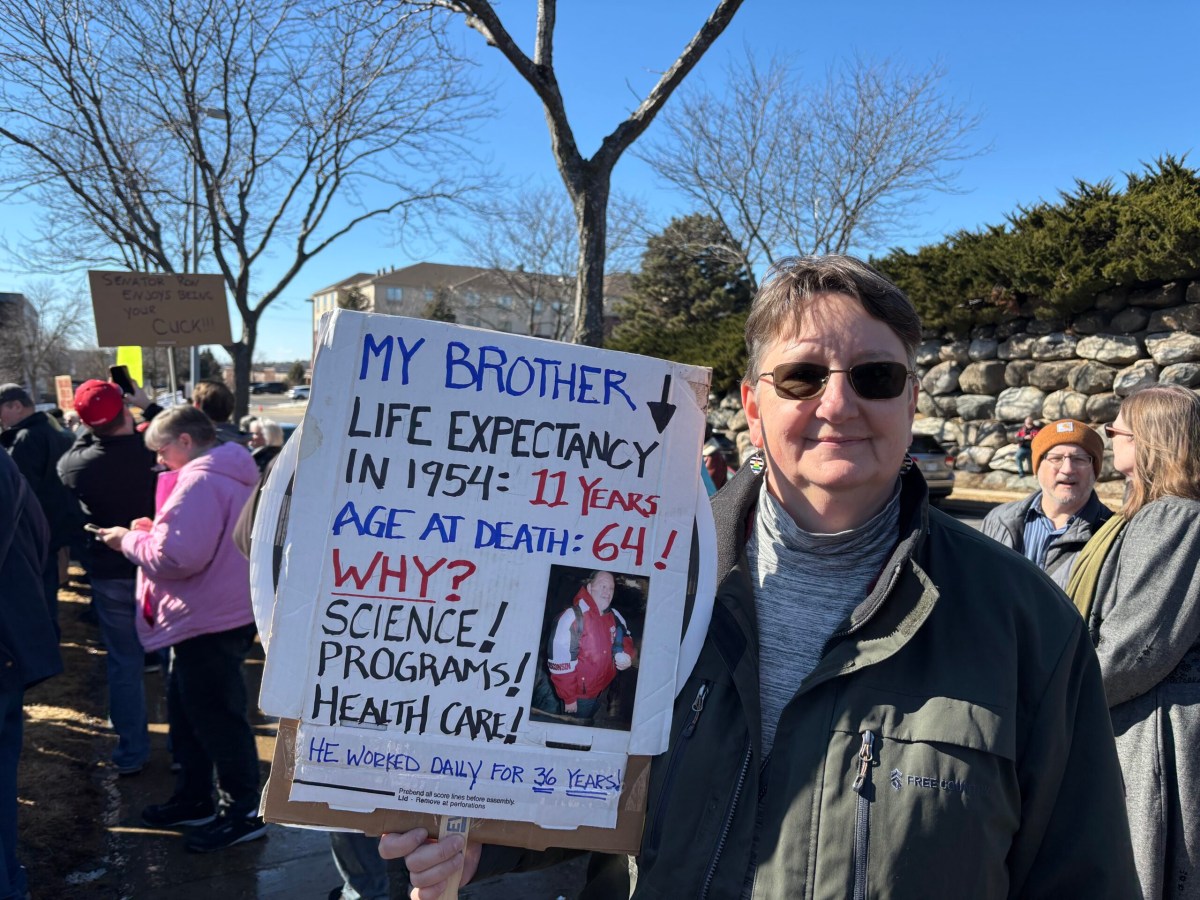

*** A reporter’s view ***

Bennet Goldstein: Water cooler conversations rarely get as quirky as strategizing the best ways to obtain photographs of cute, occasionally destructive rodents. But for nearly a month it was all I could discuss.

From equipment purchases to road trip plotting, our team’s preparation to spot a beaver was either a lesson in steadfast resolve or overkill.

With a car weighed down by plenty of granola, trail mix and Goldfish crackers, Wisconsin Watch photojournalist Joe Timmerman, videographer Trisha Young and I spent a stretch of October driving through Wisconsin’s Driftless Area and Central Sands to report a series of solutions-focused news stories. We sought to learn how beavers and their dams could mitigate severe flooding and drought, which Wisconsin and other Midwestern states increasingly face due to climate change.

I could not write about beavers without capturing one on camera, a task that has even on occasion flummoxed The New York Times.

Thankfully, a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network helped fund this undertaking.

We splashed through streams, bushwhacked through brush and hopscotched through reed grass to locate dry land where we might capture an image of our elusive furry target.

***

Last summer, I took a reporting trip to Viroqua for a different story with colleagues from the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk. There, former Vernon County Conservationist Ben Wojahn described a dilemma facing western Wisconsin communities as they consider removing failing flood control dams constructed by the federal government in the mid-1900s.

Maintaining the structures would cost more than their value, according to evaluations, but cutting gaps into them without backup protections left residents feeling insecure and unprepared for future floodwaters.

In an ideal world, Wojahn suggested, the county could bring in wood-chomping beavers to slow the flow by building nature’s dams.

What would that take?

Beaver relocation has happened before. Natural resources officials in Idaho and California famously parachuted the critters into hard-to-reach mountainous regions in the late 1940s and 1950s.

Such measures probably don’t make sense in Wisconsin, where beaver colonies polka-dot the state.

But how to find one?

Scientists warned me spotting beavers in the wild is exceptionally difficult, adding that they are typically active in the wee morning hours and at dusk. Their astute smelling and hearing senses warn them of peepers.

Then again, these researchers had not attempted to disguise themselves as piles of grass.

I initially considered purchasing ghillie suits, but the thought of spending hours commando-crawling in an outfit meant to resemble foliage sounded unappealing.

We ruled out the prospect of wading into lake shallows because Joe had rented a camera lens worth $10,000. Shrouding ourselves beneath synthetic netting would create too much noise when we stopped to pick our noses or stretch a hamstring.

I turned to wildlife photographers.

Blogs offered many tips. One professional recommended hiding in shrubbery and shadows, but he urged the adventurous to be wary of ticks.

Then it dawned on me I might be overthinking this exercise. I could instead take inspiration from hunters who have plenty of tools for quietly stalking prey. I settled on a pop-up blind and silent swivel chair.

We needed only to locate a beaver lodge and lurk.

***

One October afternoon, Joe and I canoed across a pond near the village of Rio. We passed pond scum and lily pad patches before arriving at a rickety duck hunting stand, its wood warped and spotted with exposed nails.

I steadied the canoe as Joe lunged for a foothold on the water-encircled platform. It wobbled under his weight. We eased the gear atop the stand as the sun hung low in the sky.

“What’s going on?” I said, bobbing in the canoe as he unfurled the blind.

Joe laughed.

“Is this the first of many firsts of the lengths to which we’re going?” I asked, recording the moment on a GoPro. “You’re going into a special wildlife viewing tent with a hunting chair and hunkering down for the next hour in hopes of spotting a rodent.”

Joe had spotty cell reception, so we agreed I would return at dusk if I didn’t hear from him first.

Birds chirped as I paddled back to the car, periodically banging into submerged logs.

I hunched in the front seat, hoping to avoid agitating our host’s yappy dogs, who might scare the beavers. Perched in the host’s living room window, the canines stared me down.

“I’m in my car so they don’t hear me or smell me,” I texted Joe.

A mix of dread and boredom set in as I waited, praying this would be our only beaver-spotting attempt.

An hour passed. Sandhill cranes warbled in the distance.

Joe texted.

“It just barely stuck its head above water then dove back down but I got pictures of one!!!!”

*** A photojournalist’s view ***

Joe Timmerman: As my heartbeat quickened I shifted the camera’s gears, quietly racing to document our first beaver sighting without disturbing the natural moment.

I’ve photographed surveyors in the world’s longest cave on 16-hour expeditions, woken up hours before dawn to see Indiana’s returned bison under the rising sun and hovered inches away from bats suffering from white nose syndrome in Texas. But I had never undertaken an assignment like this.

When Bennet asked how I felt about the lengths we had taken to photograph these cunning Castorids, all I could do was laugh.

Spend pieces of a month traveling across south-central Wisconsin’s beautiful landscape to prove skeptical experts wrong — and serve our readers — by returning with photos of North America’s largest rodent?

I was all in.

After our first surprise sighting near Rio we tested our luck at an additional site.

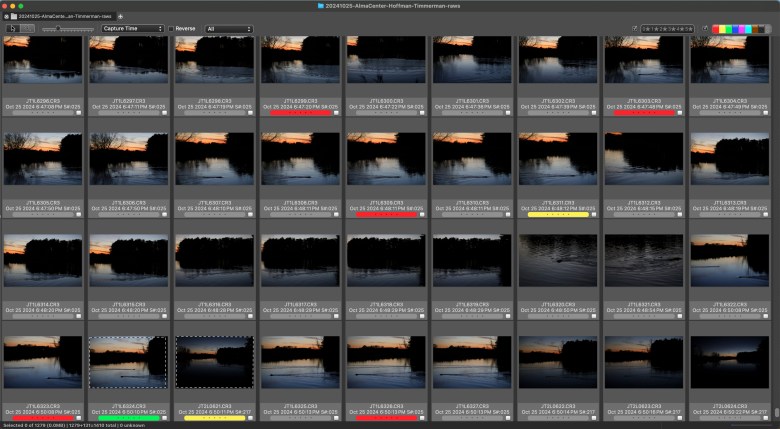

A shared hunch told us we could return home with an even better image. A few days later when we visited Jim Hoffman’s wide-spanning property at Goose Landing, I descended again into Bennet’s hunting tent before dusk.

An hour passed. The sun’s setting silhouetted the once-golden, green and yellow surroundings. Then another 30 minutes. My eyes darted between the beavers’ lodge across the pond and their trail to some felled trees nearby that Hoffman had showed us.

A slight movement caught my attention. My eye recognized the unmistakable slicked-back head of a beaver swimming across the pond. Then a second head popped up, and a third.

I zoomed in all the way, pushing our old company camera to the max in the darkening conditions. The mere seconds of opportunity etched the beaver images into the memory card before the animals disappeared beneath the water’s surface.

I waited another 30 minutes before calling it quits due to the lack of natural light. I stepped out of the tent and began packing up our gear, somewhat content but wanting more.

That’s when I saw a beaver swimming directly toward me. I fumbled to pick the camera off the ground, manually spinning the sight into focus when the beaver’s tail slapped the water, sounding a thunderous echo that made me jump.

After spending 11 hours that day making over 1,200 images, I couldn’t believe my sleepy eyes. I flipped through the first few pictures of the tail slap only to discover they were comically out of focus.

Moments later, a reprieve. The beaver re-emerged, seeming to look at me as it swam nearby — offering a fresh opportunity to make a better picture.

“All three of them are swimming like 20 feet away from me right now slapping their tails,” I texted Bennet and Trisha as they hid in their car.

“You could probably walk over and come see them.”

After all our silent stalking, the beavers had found us. Rather than rushing away, though, they were lingering — slapping the water to warn others of our presence. As the evening’s first stars appeared above, two swam parallelly in the pond below, putting on a show in trying to shoo us away.

“On our way!” Trisha replied.

*** A videojournalist’s view ***

Trisha Young: By the time Bennet and I rushed to the pond where Joe was photographing, about five or six beavers were making their rounds on the water. Our arrival seemed to increase their resolve to show us who was boss.

Thwack! The sound of the tail slap made me jump, stopping all of us in our tracks. A short while later, another thwack, then another. The beavers would beeline toward us, slap, then circle back and repeat the admonition.“What brave creatures,” I thought. Their boldness was intimidating, and the idea of being tail-slapped or bitten by their massive teeth was terrifying. Yet I was truly starting to like these hydraulic engineering rodents.

Bennet assured Joe and me that beavers would struggle to catch us on land. So I imagined falling to my fate into the dark, beaver-infested waters.

I’ve interacted with beavers before, always while kayaking. I was accustomed to the tail slap, which I always interpreted as a signal that I should keep it moving. But this was something special: a whole colony of beavers.

As I watched one pair of beavers swim side by side — one small, one large — I wondered whether Mama Beaver was showing her youngster how to lay down the law and make their authority known.

The sky turned far too dark for our cameras. We remained captivated by the furry varmints’ antics for about half an hour before finally obliging to their demand.

We headed back to the car, giddy with excitement despite the tiring day reporting at Goose Landing. The encounter was invigorating, even if our cameras couldn’t fully capture the magic we witnessed in the darkness.

The interaction reminded me of something Hoffman emphasized as we traversed the land with him: Beavers have been here for thousands of years.

The Ojibwe tell stories of Amik, a giant beaver who was given an extraordinary tail and reshaped land across the Midwest. In these stories, the beaver holds a place of significance alongside the wolf, bear and muskrat.

The fur trade in Wisconsin centuries ago decimated millions of beavers and other fur-bearing animals, forever altering ecosystems and Native livelihoods. Tribes were forced to compete with traders for resources, disrupting traditional ways of life.

Now, another shift is underway in wetland conservation, reviving a story about the symbiotic relationship between beavers and humans. I was grateful to glimpse these creatures and document how humans are trying to mimic their engineering to restore Wisconsin wetlands.

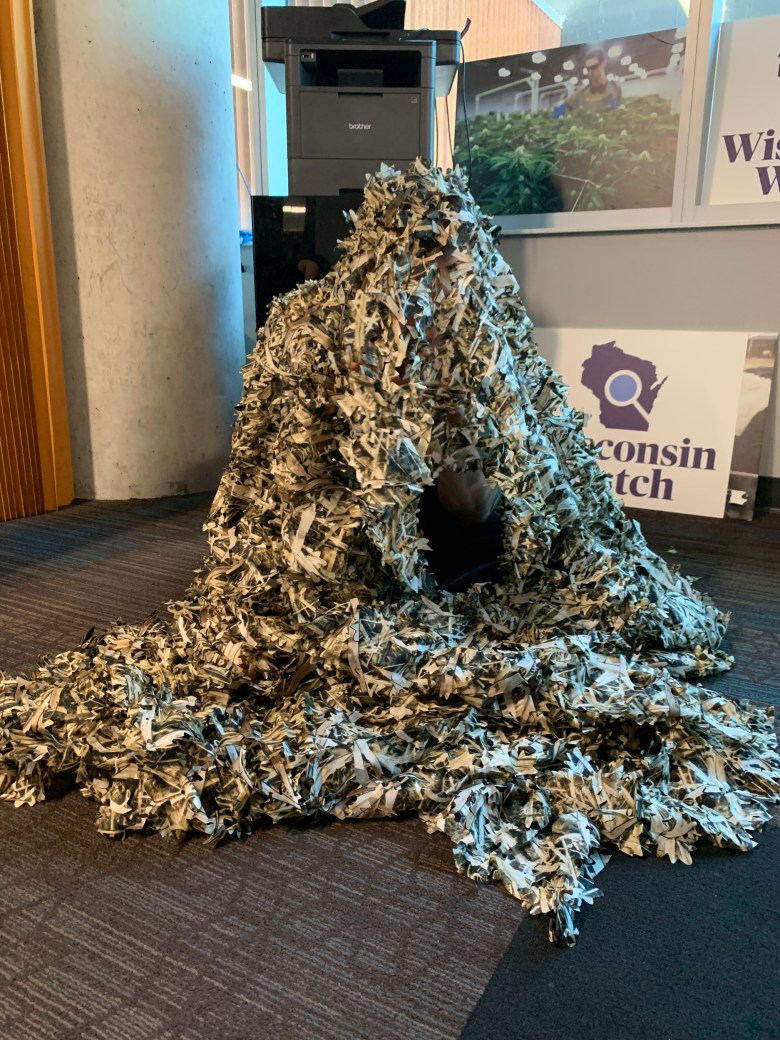

Wisconsin Watch is a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom. Subscribe to our newsletters for original stories and our Friday news roundup.